The Road from Excellence to Expansion at American Universities

By Earl H. Tilford

The 1960s

Every journey starts somewhere. In American higher education the trip to today’s diverse, equitable and inclusive “woke” universities that embrace an expansion model for enrollment began in the autumn of 1960. Notably, that was the first year there were more college students in the United States than there were farmers.[1] During the 1950s, visionary college and university presidents anticipated the looming wave of students born after the Second World war soon to be dubbed the “Baby Boom” generation. Some of those presidents built new dormitories and classroom buildings and mobilized alumni to elicit financial support to meet anticipated growth challenges.

Politically, 1960 serves as a historical watershed marked by Democrat John F. Kennedy winning the presidency. On January 20, 1961, in his inaugural address President Kennedy proclaimed the arrival of “A new generation born in this century” and prepared to “bear any burden” to defend liberty. The exclamation point was “This we will do and more.” Many young baby boomers admired Kennedy’s vigor, sense of humor, and thought him “cool.” Being both smart and educated also became cool and that meant going to college.

The new generation born in the 20th century, reared in financial hardships of the Great Depression, and tempered by war determined to provide their children—the baby boomers—opportunities a hard history denied to them. For that first wave of boomers the second stanza of folk singer Bob Dylan’s “The Times They Area A-Changin’” became an unheralded generational anthem. As for the future of higher education, Bob Dylan warned scholars “who prophesize with your pens” to beware “for the loser now will be later to win.”

The Stirring

In 1960, a handful of students at the University of Michigan founded Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), the New Left’s child of the League of Industrial Democracy’s Intercollegiate Socialist Society established in 1905 by Upton Sinclair, Walter Lipmann, Clarence Darrow, and Jack London.[2] On June 16, 1962, led by student Tom Hayden SDS members met in Port Huron at the United Auto Workers retreat where they wrote the “Port Huron Statement” predicting universities as founts for social change. The document became a manual for creating academic chaos by erasing class lines separating professors from students, and by grade differentiation classifying students by scholarly attainment or lack thereof. Education would become a collaborative effort rather than a system by which educated professors informed and taught students.[3] Good intentions expressed in the rhetoric of social justice obscured the goal of radical societal change. SDS envisaged higher education as a tool to affect radical change.

In the late spring of 1963, as the baby boom generation prepared to enter their high school senior year in the coming autumn, the University of Alabama remained the American academy’s last bastion of racial segregation. That changed on June 11, 1963, when two Black students strode past a defiant Governor George C. Wallace to crack the racial barrier at the state’s flagship university. While this racial barrier fell peacefully, such was not the case an hour’s drive east in Birmingham where Blacks, most of them youngsters, took to the streets demanding job opportunities beyond janitorial services, shoe shinning, and elevator operating. Fire hoses and police batons delivered violent images underscored by the bombing of the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church on Sunday, September 15, 1963.

After graduating from their still rigidly segregated schools, many Alabama boomers would be headed for college. I was among them and bound for the University of Alabama partly because its history department was recognized for its quality. The murder of President John F. Kennedy and his burial on the Monday before Thanksgiving cast a shadow that hovered without totally shrouding our generation’s optimism.

In the autumn of 1964 when boomers flooded into higher education, the ideological complexion of most college and university professors ranged between moderately liberal to conservative. Frank A. Rose, an ordained Disciples of Christ minister, had become president of the University of Alabama in January 1958. In large part, Alabama’s trustees hired Rose to usher the university through desegregation. Newly inaugurated Alabama Governor John Patterson, however, stood staunchly against racial integration. President Rose focused on building infrastructure to accommodate the wave of boomers scheduled to arrive in the Fall of 1964. New dormitories and 1963 opening of Marten ten Hoor Hall dedicated to the liberal arts aside, the newly enrolled boomers were told two-out-of-three would endure to graduate in May 1968. The freshman rumor mill held core curriculum courses existed to “weed out the chaff.”

President Rose emphasized the “pursuit of academic excellence.” In the 1960s, the University of Alabama was on a three-point grading system. The average grade for males ranged between 1.3 and 1.5 (C- to C). Females scored slightly higher at 1.5 to 1.7 (C to C+). [4] With the women’s liberation movement at its breaking of dawn phase, many coeds still majored in elementary education, home economics, or nursing. Male students opted for traditional liberal arts majors, pre-law, pre-med, or engineering, and business majors. Higher education focused on preparing students for productive lives and responsible citizenship. Tuition at Alabama remained reasonable rising from $150.00 a semester in 1964 but rising to $175.00 a semester in September 1965. Low interest loans were available via the National Defense Education Act, co-sponsored by Alabama Representative Carl Elliott and Senator Lister Hill in 1958.[5]

In the 1960s, a significant portion of baby boomers were the first in their respective families to attend college. They embraced the idea that a bachelor’s degree provided a key to the “American Dream” culturally accepted as consisting of a good career, a traditional family with two or three children living in a $25,000.00 house with a two-car garage. Students for a Democratic Society decried that concept of America and envisioned higher education as an instrument for radicalizing America.

Then the United States became involved in a in Southeast Asia. The Vietnam war played a pivotal role in changing the culture on campuses throughout the United States. The ignition point was in March 1965 when President Lyndon Johnson initiated Operation Rolling Thunder, the bombing of North Vietnam to compel its communist regime to stop supporting a growing insurgency in South Vietnam. The first sorties were flown on March 2, 1965. Three weeks later the first anti-war “teach-in” was held at the University of Michigan.[6]

To keep the conflict limited and thereby prevent a wider war with China or the Soviet Union, President Johnson did not ask for a declaration of war and opted not to call up Reserve and National Guard components. The Selective Service Commission provided conscripts through 4,000 local draft boards. Peace-time draft laws provided the 2S deferment for draft-age men continuing their education. In 1967, changes in the draft law eliminated graduate deferments for most liberal arts fields to include history, political science, and English among others.[7] This happened as the first wave of male boomers entered their senior year. Extra years of 2S deferments for graduate school were no longer guaranteed.

Fear of conscription and the possibility of a year serving in Vietnam drove many young male collegians to seek safe havens. Running to Canada appealed to many, but that was a long way from Alabama and cowardice was not a “Southern” male characteristic. The University of Alabama offered Army and Air Force Reserve Officer Training Course options leading to an officer’s commission upon graduation. Being sworn into ROTC technically put you in cadet status with a draft exemption. The other alternative was service in the Alabama Army or Air National Guard. Admittance to either favored White males with political connections. At an October 2010 University of Alabama conference focusing on the 40th anniversary of student unrest following the May 1970 shootings at Kent State University, former Governor Don Siegelman who served as Student Government Association President for the Class of 1968, admitted had he not been able to enlist in the Alabama Air National Guard he might have sought asylum in Canada.[8]

During the 1960s, graduate programs in the liberal arts expanded exponentially. According to historian Oscar Handlin, American graduate schools produced 5,884 doctoral (PhD) degrees in the decade of the 1960s. By comparison, in the 87 years from 1873 to 1960 American universities produced 7,695 Ph.Ds.[9] Since graduate schools had expanded to accommodate the increased numbers of students seeking continued draft deferments, the question became how to sustain existing programs? Lowering standards to admit large numbers was one option. Accordingly, the one foreign language competency for the MA in history at the University of Alabama was eliminated and the two-language requirement for the doctorate reduced to one. Another alternative was to encourage females to apply. Traditionally, women seeking graduate degrees had gravitated to the Education departments for degrees in elementary and secondary education.

Although the draft-driven drama continued to the end of the decade, the need for conscripted soldiers declined with President Richard M. Nixon’s “Vietnamization” strategy focused on withdrawing all US combat and support forces from South Vietnam by January 20, 1973, the end of his first term in office. In 1971, the Selective Service Commission went to a lottery based on month and day of birth. Meanwhile, as forces committed to Vietnam drew down, draft quotas dropped substantially, and peace returned to most campuses.[10] But the damage to higher education was underway.

Graduate schools from the Ivy League and in publicly-funded universities across the nation continued to grind out newly-minted Ph.D.’s in search of job opportunities. Additionally, to sustain institutional growth, a plethora of new graduate programs emerged. American Studies, African American Studies, Women’s Studies and other “gender studies” programs gained traction after the late 1960s and into the following decade. Throughout this time, the American academy drifted increasingly to the left. It took a little longer at the University of Alabama.[11]

Although topics attendant to slavery, the Civil Rights movement, women, Latinos, and various sexual orientations could have been addressed as topics for research and study in traditional departments like history, English, political science, philosophy, and psychology, new programs were established. Each of these created their own bureaucratic constituencies. Administration positions to oversee these programs proliferated. During the 1960s and 1970s, liberal arts scholars trained between the Depression and immediately after the Second World War moved into senior academic ranks. Department chairs and deans emerged from this cohort as well. In 1969 the Carnegie Commission on Higher Education indicated 45 percent of faculty held left or liberal views, 27 percent were centrists and 28 percent either moderately or strongly conservative. In 1999, thirty years later, another Carnegie survey found there were five leftist professors for each right-of-center scholar. For those hired after 1969, the range was 7 to 1.[12]

The American academy allowed this to happen. Moderately liberal and many centrists to conservative scholars, were anxious to demonstrate their tolerance for contrasting opinions, perhaps believing neo-Marxists shared similar outlooks. In some cases, to solidify their research and publications bona fides, these senior scholars turned over the burdensome job of recruiting new faculty hires to junior department members scrambling for tenure and ready to please even if it meant muddling through a burgeoning number of job applications for each available position. By the early 1980s, a job opening might elicit up to a hundred or more applications. Additionally, the Chronicle of Higher Education and other journals where jobs were advertised required job descriptions to include “Women and minorities especially encouraged to apply” as part of a concerted effort to introduce more diversity throughout the academy. With large numbers of qualified applicants to review, a sure way to “cull the chaff” was to give the nod to a female or minority applicant. Many newly minted scholars faced a series of adjunct jobs without benefits and little hope of permanence. Some might find jobs with think tanks or something in the public-service sector working for local, state or the federal libraries or history programs.

Getting “Woke” at Bama

It took a while for the “woke” movement focused on social justice, commitment to “Diversity, Equity and Inclusion (DEI), with concomitant approval of the goals of Black Lives Matter and other groups to reach the sylvan campus of the University of Alabama. After all, Bama with a student population of over 38,000, since 2011 boasted the nation’s largest fraternity and sorority community with 34 to 35 percent of undergraduates opting to “Go Greek.”[13]

A recent Heritage Foundation report titled “Diversity University: DEI Bloat in the Academy” indicates over 40 universities are more involved in DEI than Alabama’s flagship university, nevertheless enthusiasm for “wokeness” is rapidly becoming pervasive. For instance, while the University of Michigan tops the Heritage Foundation’s list of DEI-committed universities with 163 DEI-designated personnel for 48,090 students, the University of Alabama with 38,100 registered for Fall 2021 classes has 31 DEI-administrated personnel overseeing related programs.[14] The ratio between DEI-dedicated personnel and tenured and tenure-track members of the history departments at Michigan and Alabama finds Ann Arbor with 163 DEI-personnel and 72 history professors (2.3-1) and Alabama with 31 DEI-dedicated personnel and 27 history professors (1.1)[15].

Granted, the words “diversity, equity, and inclusion” harken to lofty ideals. Since words matter and history is written with words, we need to explore how DEI advocates define these terms. “Equity” does not mean equality of opportunity but equality in outcome to achieve a predetermined quota focused on race, gender, ethnicity, and sexual orientation. According to 2017 document issued by the Halualani Associates titled, “Diversity Mapping Report: University of Alabama (UA)” a diversity effort is “Any activity or program that promotes the active experiences as constituted by gender, socio-economic class, political perspective, occupation, and language, among others, as well as any activity or program that brings together any of these aspects.” Halualani Associates defines a diversity course as “[one] that focuses on issues and topics related to various cultural groups, backgrounds or identities and experiences, and/or promotes the larger importance of diversity the larger importance of diversity, difference or cultural sharing for the public.” Accordingly, “All diversity-related courses are primary which means the diversity content constitutes the dominant focus of the course.”[16] (Underscore added)

The University of Alabama Honors College purports to recruit the “creme de la crème” among the student body for inclusion in its exclusive seminar courses with a student-to-faculty ratio of 15-to-one.[17] According to its website, “The University of Alabama Honors College is committed to cultivating a scholarly community that celebrates values of diversity, equity and inclusion.” To do so, according to a December 2020 website posting, “The University has made the admissions process more accessible by making standardized test score submission optional. Standardized tests are barriers for students who cannot afford to take the tests multiple times, or do not have access to test preparation resources.” According to Honors College Coordinator for Student Recruitment Brandon Chalmers, “The research and the data suggests that sometimes these tests are biased against students of color.”[18]

The University of Alabama resides on one of the nation’s most attractive campuses. For the fourth year in a row the number of students enrolled from other states exceeds the number of instate students. Even when there was a time the primary mission of this flagship university involved the “pursuit of academic excellence” it never—nor would it ever—academically rival southern “Ivies” like Vanderbilt, the University of Virginia, or the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill. Nevertheless, if the University of Alabama is to remain the “Capstone of Higher Education” in the state of Alabama and compare favorably with other southern institutions of higher education like Auburn University, the University of Florida, and Texas A&M it needs to diminish its commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion and refocus on the pursuit of academic excellence. To do that requires a commitment the quality of scholarly attainment in faculty recruiting and indications of academic capability for recruiting students rather than meeting goals for demographic distributions and ever increasing enrollment.

[1]Todd Gitlin, The Sixties: Years of Hope, Days of Rage (New York: Bantam Books, 1898), 21.[2] Harold Lewack, Students in Revolt: The Story of the Intercollegiate League for Industrial Democracy (New York: League for Industrial Democracy, 1933), 6.

[3] “Port Huron Statement for Students for a Democratic Society”, 1-2, https://course.matrix.msu.edu/whist306/documents/huron.html. Accessed August 21, 2021.

[4] “Undergraduate Scholarship Averages, Men and Women, Fall Semester, 1967-1968,” F. David Mathews Papers, General Students Personnel File, Hoole Special Collections, University of Alabama.

[5] Wayne Flynt, Alabama in the Twentieth Century (Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2004), 69.

[6] See: George Herring, America’s Longest War: The United States in Vietnam, 1950-1975 (New York: McGraw-Hill, inc. 3rd Ed., 1996), 140-44; and Nancy Zaroulis and Gerald Sullivan, Who Spoke Up? American Protest Against the War in Vietnam, 1963-1975 (New York: Holt Rinehart and Winston, 1985), 37-38.

[7] Joe P. Dunn, “Draft,” in Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War, Vol. I, A Political, Social and Military History, Spencer E. Tucker, ed. (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC CLIO Books, 1998), 177-78.

[8] “Days of Rage Conference,” University of Alabama, Capstone Hotel, October 9,2010, Tuscaloosa, Alabama, Tuscaloosa News, October 10, 2010, 1.

[9] In Mary Grabar, Debunking the 1619 Project: Exposing the Plan to Divide America (Washington, DC: Regency History, 2021), 48.

[10] Thomas C. Thayer, War Without Fronts: The American Experience in Vietnam (Boulder, CO: Westview Press, 1985), 119-121.

[11] Charles Murray, Coming Apart: The State of White America, 1960-2010 (New York: Crown Forum, 2012), 25.

[12] See: John M. Ellis, The Breakdown of Higher Education: How It Happened, The Damage it Does, and What Can be Done (New York: Encounter Books, 2020), 32-33; Mark E. Levin, American Marxism (New York: Threshold Editions, 2021), 260-61

[13] “University of Alabama Fraternity and Sorority Life,” https://ofsl.sa.ua.edu, accessed March 8, 2018.

[14] James Paul, “Diversity University: DEI Bloat in the Academy,” Heritage Foundation Report (Washington, D.C.: Heritage Foundation, 2021) 5.

[15] Ibid.8.

[16] “Diversity Mapping Report: University of Alabama,” (Redwood, CA: Halualani Associates, 2017), 14.

[17] A University of Alabama Honors College I taught in 2010 titled “Clausewitz and Sun Tzu: The Roots of Modern Strategy” had five of the 15 students drop the course on day one after they received a syllabus that specified 600 pages of reading and writing a 20-to-25-page research paper.

[18] Brandon Chalmers, “University of Alabama Recruitment and Admissions’s (sic), Fall 2020 DEI Initiatives,” December 1, 2020, https://honors.ua.edu.

Earl Tilford earned his BA and MA in history at the University of Alabama and his PhD in Modern American and European Military History and Soviet and East European Politics from George Washington University. During his Air Force career, he served as an intelligence officer during the Vietnam War and a nuclear targeting officer at Headquarters, Strategic Air Command. He also taught at the Air Force Academy and Air War College and served as Director of Research at the US Army’s Strategic Studies Institute. From 2001 to 2008, Dr. Tilford taught history and national security courses at Grove City College. Earl is the author of three books on the air war in Vietnam. In 2014, the University of Alabama Press published his latest book, Turning the Tide: The University of Alabama in the 1960s. He is a previous contributor to Alabama Heritage Magazine and lives in Tuscaloosa.

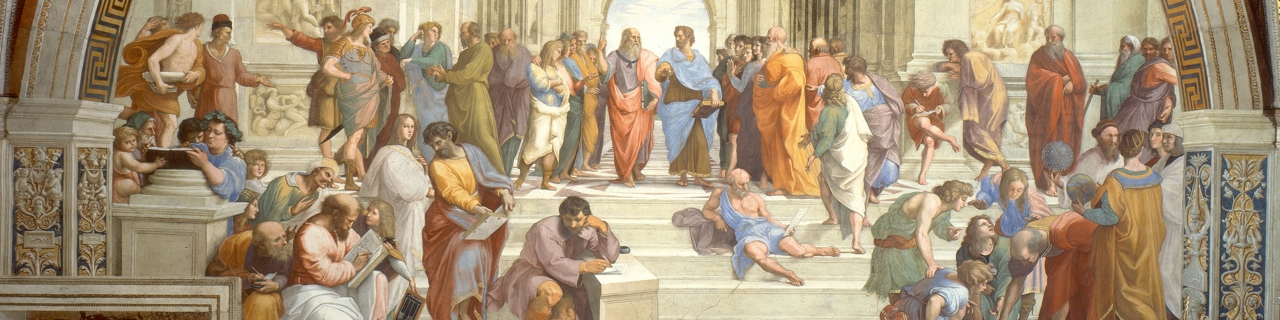

Photo by Pixabay from Pexels